By Scott Teesdale and Joseph Agoada, InSTEDD

The 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa illustrated the intensity and complexity of an international response to a regional epidemic that posed a threat to the rest of the world. With the death toll in West Africa climbing daily, the international community worked to respond with ingenuity and rapid assistance.

Public health organizations around the world mobilized, sending doctors, nurses and others to help in West Africa. Government officials frequently traveled to affected countries to help support the response. Business people continued work-related travel, and seeking reprieve from the outbreak, West Africans traveled to other countries to stay with loved ones.

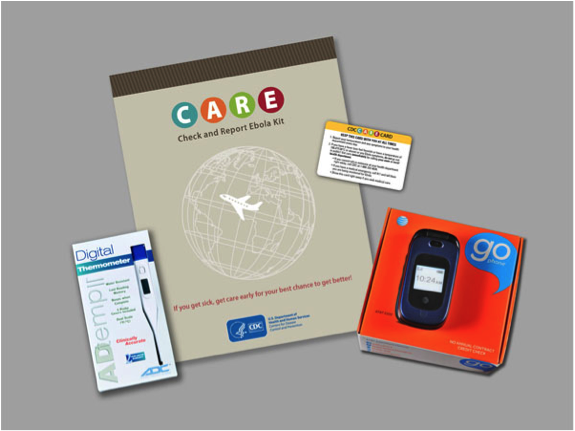

As trips continued, the issue of travelers arriving to the United States from countries with Ebola outbreaks prompted a recommendation from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that state and local health authorities monitor travelers for Ebola symptoms. This request led to the design of a new technology called the Check and Report Ebola (CARE) Hotline.

The hotline’s creation and pilot during the Ebola outbreak highlighted the importance of augmenting public health efforts with both innovative technology and agile skill sets for greater preparedness when the next global health threat emerges.

Pictured above: Ebola CARE Kit, including a brochure, thermometer, ID card and working cell phone. CARE Kits were distributed to travelers to help them submit daily health reports.

Introduction

In late October 2014, state, local and territorial health authorities across the United States began monitoring travelers arriving from countries with Ebola outbreaks. Because symptoms of Ebola can appear anywhere from 2 to 21 days after exposure to the virus, an infected individual could cross borders with no sign of the disease. CDC therefore recommended that each traveler who might have been exposed monitor themselves for signs and symptoms of Ebola for 21 days after their last possible exposure and report daily to a U.S. public health authority.

To collect the daily health reports, U.S. state and local health authorities needed resources beyond their existing capacities. They used centralized call centers, SMS text reporting of symptoms, mobile applications, web-based reporting systems and in-person health checks.

As CDC looked for ways to support the public health authorities tasked with monitoring travelers, the San Francisco-based Skoll Global Threats Fund reached out to CDC and offered support. With Skoll’s help, CDC and InSTEDD began to work on a tool to ease the burden of post-arrival monitoring. The aims of the collaboration were to:

- use existing open-source tools to develop and deploy a mobile solution that supported travelers asked to self-report their daily health status,

- provide public health authorities with timely and accurate data that met CDC’s monitoring recommendations, and

- reduce bottlenecks in getting travelers support they needed (such as information on the disease or a referral to a medical professional).

An innovative solution for monitoring health of arriving travelers

The CARE Hotline allowed travelers to submit their daily health reports to an interactive voice recognition (IVR) hotline, making the monitoring process faster and more efficient for both travelers and public health authorities, and allowing the data to be more easily organized and used.

Travelers called the hotline daily and followed prompts, answering yes or no to questions about their health status. An automated SMS text reminded travelers to check and report their health status. Additionally, the hotline alerted public health authorities to potentially ill travelers and gave travelers information to keep them safe and knowledgeable about the outbreak. A health worker was on call 24/7 in the event that any participant indicated illness or asked to speak with a live person.

CDC piloted the hotline with CDC employees returning from deployments to West Africa. An evaluation of the pilot found that the hotline garnered high user satisfaction, required minimal reporting time from users and was an easily learned tool for monitoring. Most were highly satisfied (90%) with the system, indicating ease of use and convenience as primary reasons, and would recommend it for future monitoring efforts.

Analyzing the hotline call log, CDC found that 94% of calls were successful and the average call time significantly decreased from the beginning of the monitoring period to the end by 32 seconds (Z score = -6.52, p=0.000). User feedback confirmed call log data; survey results indicated that users became more familiar with the system, and found it easier to use, from the beginning to the end of their monitoring period.

You can read more about the pilot evaluation in a recently published report in the Journal of Medical Internet Research Public Health and Surveillance. Check it out here: https://publichealth.jmir.org/2017/4/e89/

Considering the impact and lessons of the CARE Hotline

“Initially, this was an effort to build a tool to support state and local health departments. As we moved further in the response, it also became clear that early engagement with tech solutions and agile approaches to design could have long-term benefits. Responses are difficult but often provide opportunities to try new things and to try them quickly. Lessons learned from those experiences can be invaluable for future outbreaks and other public health challenges.” – Abbey E. Wojno, PhD, CDC public health advisor

Key insights from the project spanned both how we as innovators approach interventions during a public health emergency as well as how technology can help to promote positive human behaviors.

Below are main lessons learned and validated assumptions we identified post-effort from the CARE Hotline innovation work:

1) Agile methodology is a valuable approach for collaborating within a rapidly evolving situation; specifically, this meant:

- Empowering a multi-disciplinary team to work together effectively: Harnessing an agile approach, our diverse set of stakeholders quickly got into the problem-solving mindset, fostered a spirit of collaboration, and were better equipped to handle ambiguity in the project.

- Using short sprints enabled incremental improvements on the innovation each week: The CARE Hotline team worked iteratively to deploy a new and tested version of the hotline each week. To do this we prioritized the most important new features or fixes based on user feedback. The team held regular sprint meetings that built in short feedback loops, encouraged stakeholder engagement, helped to confirm or revise assumptions, and resulted in a high-quality mobile solution.

We also set up both a staging and a production version of the system so we could test new improvements or features for the next iteration while still maintaining a seamless experience for users.

- Getting a basic version of the innovative solution in front of users quickly: The agile approach enabled CDC and InSTEDD to develop a tool rapidly and gave us the flexibility to make changes while we implemented the system. The CARE Hotline moved from an idea to a tested, functional system within weeks. We also avoided a lot of wasted effort and resources by testing assumptions early and often with minimally viable early versions of the tool.

- Building innovation skills sparked long-term impact: A lasting result of the CARE Hotline work was that the CDC staff gained new agile project management skills and abilities to advance innovation. For some, this project was their introduction to agile design. This exposure during the Ebola outbreak prompted interest in additional training and implementation opportunities around agile design, design thinking, and lean start-up approaches to public health activities. Here we learned that increasing the ability to innovate can be just as valuable as the innovation itself.

2) Using existing free and open-source software gave the team a head start. The CARE team did not try re-invent the wheel with the innovation. The focus was more on the content and interactions with returning travelers rather than trying to build something from scratch.

To do this quickly we used:

- Verboice for the IVR hotline,

- mBuilder for the SMS interactions, and

- Google Sheets to analyze anonymized data on the fly.

3) Philanthropic groups played an important convening role. This effort demonstrates the role that philanthropy and established partner networks can play in helping even the largest institutions stay nimble and explore innovative techniques. Skoll Global Threats Fund brought CDC and InSTEDD together and enabled them to get to work quickly.

What’s Next — Continuing the innovation journey for the next public health emergency response

InSTEDD is now working to refine the CARE Hotline, preparing it for the next emergency or for other partners who may wish to use it for more routine health monitoring projects. We believe that many other public health or development projects can benefit from a mobile tool that can track health status and is able to identify and support those at high risk. We are excited to add this new tool to our open source platform.

We expect the public version release of the CARE Hotline tool to be ready for public health and development groups to use in early 2018. We are looking for partners who want to test and pilot the system and tell us how it could best meet their needs. Please contact InSTEDD if you would like to learn more at: info@instedd.org.