A Missive from Brooklyn, 2002

In 2002, I got my first job out of college as a community health worker in Brooklyn. Born to a family of seven kids, we couldn’t afford university tuition and so I graduated with a $100k lump in my throat. The Americorps program offered to repay some of my loans and provide an $800/month stipend in exchange for working full-time in one of New York City’s poorest and most diverse immigrant neighborhoods, Sunset Park. I thought that I was getting an incredible deal.

My grandmother

As the child of newcomers, I have always felt at home in America’s immigrant communities. I see my own grandmother, our family’s matriarch, in every weary-worn woman who wields respect from neighborhood bad boys with one hand and sows together a world of serenity for bookishness types like myself with the other hand. She showed me that a family’s and community’s strength comes from these bossy ladies who may not have even finished high school but can smell bullshit from a mile away.

On my first day on the job as a community health worker, I arrived at the church basement that would serve as my base of operations. I was paralyzed with the knowledge of being badly under-qualified. I wore my nicest dressy clothes to work everyday, in an attempt to at least appear qualified. Our neighborhood did not need a second-generation know-it-all recent college graduate with some pretty good ideas about social justice, feminism, and health equity but no real world wisdom. With time, I developed a sort of wisdom-Judo, finding the neighborhood leaders who actually knew what they were doing and engaging them in finding answers to individual, family, community, and institutional problems. I struggled to bridge the gap between Brooklyn’s megalithic health care system and the people who needed care most. I saw needless death and pain at the hands of medical providers and administrators. I watched rope-a-dope moves from newly arrived families who tried to navigate the bureaucracies that stood in their way. I witnessed the everyday consequences of our families’ and communities’ violence against women, the real face of institutional racism, and the utterly complex role of community health workers who must put themselves in the middle of it all.

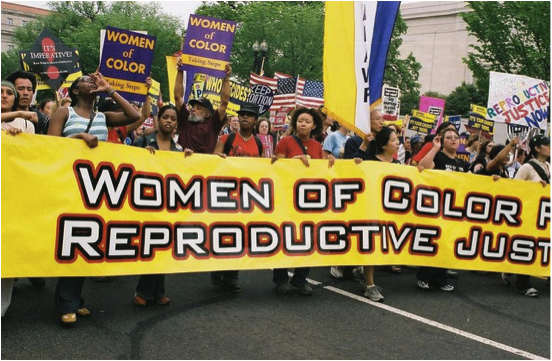

A march that I helped organize for immigrant women’s health issues

For years, I worked as fighter, peacemaker, and caretaker. And, I can tell you this: it is exhausting, pitifully paid, and incredibly empowering work. I had an ulcer, survived on food stamps, and constantly tested the limits of my humility and resourcefulness. There was no such thing as work-life balance. In my opinion, everyone, especially physicians and health ministry leaders, should have to work as a community health worker.

Ramping Up to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals

In truth, all health systems around the world need community health workers. Nearly all countries in the world have shortages of health workers and inequities in access to vital health services. For the world’s poorest countries, the scarcity of human resources is fueled by the devastation of HIV/AIDS, migration of qualified health workers to richer countries, and inadequate investment in national health systems. Meanwhile, the global community has higher demands and more ambitious hopes for health systems in poorer countries than ever before. To achieve the Millennium Development Goals, new targets for HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention, and other global aims, global health policy organizations are leading a series of campaigns to further engage community health workers (CHWs) around the world.

Millennium Development Goals – World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2008

It’s an exciting time. But, I am also scared to death for the hundreds of thousands of CHWs around the world who are being asked to shoulder the burden of the world’s health needs. CHWs are paid starvation wages because their passion for community and justice is thought to be pay enough. Health systems hand down standards and policies for controlling their actions with no consideration for empowering their actions. CHWs are fired and forgotten for the same traits that inspired them hire the CHWs, the fact that they come from community and not the universities and towering institutions of the world. Community health workers take care of everyone and are cared for by no one: they are the under-valued moms of the health system.

mHealth & Community Health Workers: 3 Tips for ICT4CHW

At InSTEDD, we are thinking a lot about the information tools that these “moms of the health system” can use to be effective and empowered. I’ve noticed a trend in punitive technologies, those apps and platforms that help health systems to identify and discipline bad CHWs without any need for human support and supervision — like an invisible fence that keeps a bad dog in a yard. And then there’s a trend in puppet master technologies, those apps and platforms that keep CHWs in line, adherent to institutional policies, and compliant to a strict regimen of services within specific disease issues – like a remote control for an automaton.

Despite my limited experience working as a community health worker and my own questions about whether I was ever an excellent one, I’d like to offer this advice.

1. Understand who CHWs are

A community health worker at a rural health center in Cambodia

Even before you begin to propose a CHW technology intervention, develop a CHW persona with a paragraph description on who this person is, an image of what they might look like, and an idea of the challenges they face every day. Start from a position of compassion and empathy and ask yourself: what tools would my mom need to shoulder the burden of health care inequity? Many CHWs are also survivors of disease and discrimination themselves, so ask: what would my mom need if she decided to dedicate her precious energy and years to the health of others? Often, the answer will bring you to advocate beyond the user interface and you will need to throw your professional weight into broader questions around how CHWs are recruited, paid, supported, and empowered in their roles. In technology projects, no one thinks it’s their place to advocate more broadly for CHWs. If you don’t do it, there’s a chance that nobody will.

2. Use empowering approaches to design & development

iLab Southeast Asia Field Support Officer, An Yon, does user testing with community health workers outside of Phnom Penh

It’s excellent to start with a position of compassion and empathy, based on your own experiences. However, your experiences of the world will be inadequate for understanding how CHWs get things done. Don’t even try to guess. Don’t ask physicians to guess. Don’t ask the ministry of health to guess. Good design and development starts from gaining insight into all users needs from their perspectives. Although monitoring user behavior is a good source of information about their true actions, it is complimented and strengthened by engaging users face-to-face and paying them the respect of asking about their lives, their jobs, how they navigate challenges, and how they build on existing resources. The fields of participatory design and participatory research have a lot to teach us about specific practices and methods.

3. Build empowering tools

A community health worker in rural Laos uses images and text messages to share information with her headquarters

Ultimately, the process of building and using information technologies must include opportunities to iteratively integrate feedback from CHWs. Whether it’s through a community advisory board, a core team of CHW users, or regular CHW surveying, tools must be improved with insights from CHWs early and often. As for developers, we often get stuck in between our ultimate client (Ministry of Health, for example) and our ultimate user (CHWs, for example). When we serve our institutional client, we build relationships that facilitate in-country work and help our organizations to stay afloat with new contracts. However, excluding ultimate end users puts us at risk for something even worse: best case scenario, you build tools that nobody wants to use or can use and worst case scenario, you build a tool that treats CHWs like dogs or automatons. Empowering tools help CHWs to bring a wealth of community knowledge, skills, and resources to bear as they solve problems that health systems have never successfully solved. Treat them like respected experts. Because they are.

A Final Wish

Eleven years after my first CHW job in Brooklyn, I have now worked in global health for eight years, I earned my doctorate in public health, I amounted $70k in educational debt, and I still can’t shake the feeling that my knowledge and experience makes me severely under-qualified for addressing health problems in the rough neighborhoods of the world. I hope that the years to come help me to repay my loans and contribute to global health technology, but always to keep the humility. I hope the same for our field.